The “Phantom” had been identified.

On the 28th June 1982, a police constable from the Warrant department of West Yorkshire Police discovered that a man named Barry Peter Prudom had failed to answer court bail following a serious assault in Leeds in January 1982. What stood out was that Prudom’s date of birth was 18th October 1944 – the same as PC Haigh had written on his clipboard. Because the close proximity of an attack in Leeds and the date of birth written on the clipboard seemed a real solid lead, photographs of Prudom – together with others – were shown to the police officer who had been injured in the shooting at Dalby Forest, PC Kenneth Oliver.

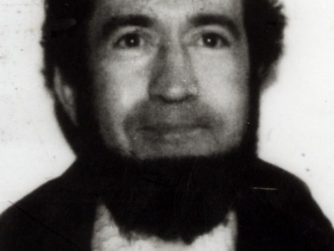

PC Oliver unhesitatingly picked out Prudom as the man who had shot him, and Prudom’s fingerprints matched those taken from the abandoned green Citroen car. Police now knew beyond any doubt the identity of “The Phantom Of The Forest”. A picture of Prudom was issued to the press and public with the warning that he was wanted for questioning in connection with the shootings, and was to be considered armed and extremely dangerous.

So now police knew the identity of the man they were hunting – but they were still no closer to finding him.

On Wednesday 30 June, police were approached by a survival expert named Eddie McGee, who was a former Army PT instructor and author of several survival textbooks. He was well-trained in the art of tracking, having learned from Aboriginal tribes in Australia and Pygmy tribes in Africa, and offered his services to assist in the hunt for Prudom. This was immediately accepted, and Mcgee and a colleague began to track the fugitive, beginning at the scene of Sgt Winter’s murder.

In the Dalby Forest area, a makeshift “hide” was quickly found that the wanted man had been using, and McGee and colleague followed tracks from it in a search that took them all of the next three days and led all over the Old Malton and Malton areas. Many of the tracks were very recent – Prudom had not left the general area, but instead seemed to be playing a cat and mouse game with police hunting for him. Mcgee was also of the opinion that Prudom was near the point of exhaustion due to being kept on the move by the constant police presence.

The manhunt moved into its endgame early on the morning of 04 July 1982, when police received a telephone call from a Mr Maurice Johnson of East Mount, Malton. Mr Johnson spoke to police at 05:45am and reported that he, his wife and adult son had been held hostage at gunpoint in their own home by Prudom since 5:00pm the previous day. He had not harmed any of them, but had tied them up. During the time they had been held hostage, Prudom had confessed to them the murders of PC Haigh, Mr Luckett, and Sgt Winter, the attempted murders of Mrs Luckett and PC Oliver, and the burglary at Mrs Johnson’s bungalow. He had left their home at 05:00am. The Johnson’s had waited for a period of time from Prudom leaving the house before contacting police, even going so far as to turn on the upstairs lights to make Prudom think they were going to bed – in case he was still watching the house.

Immediately the area was surrounded and the village sealed off, and by 07:30am, McGee and an armed escort had began to search the rear of the Johnson’s house for footprints. Mcgee found one that was very fresh almost instantly, and followed tracks across the grounds of the nearby Malton Lawn Tennis and Bowling club that terminated near the remains of some fencing panels that leaned against a stone wall and that were covered with brambles and bracken. Mcgee, whilst stealthily examining the scene, noticed that whilst the majority of the brambles were thick with early morning dew, there was a black patch where the dew had been brushed off. Suspecting that he was hot on Prudom’s trail, Mcgee was to later describe the moment:

“I took out a probe and went forward, feeling the ground There was a little bit of blue plastic bag which casually moved to one side. I put my hand forward to lift up the probe and as I did – suddenly a foot few back and sent me rolling back. I jumped in the air, but didn’t shout. I retraced my steps and disappeared around the back of the wall, then motioned to the officers “there!” – we’d got him” – Eddie McGee

Armed police soon surrounded the area where Prudom had been cornered and shouted to him to surrender – but there was no answer.

Shortly afterwards, Chief Inspector David Clarkson of West Yorkshire Police, and Inspector Brian Cheton of North Yorkshire Police – both armed officers – approached the fencing panels and attempted to move them away from the wall. The response was a shot fired from inside the fencing, and both officers moved back to a safe distance. They did, however, fire four shotgun rounds in return. Further calls to surrender were again met by silence, so further shots were fired and two percussion grenades were thrown. The officers then returned and again attempted to remove the fencing panel – and this time were successful. Beneath it, Barry Prudom lay dead, with a pistol on his chest pointing upwards. He had been stopped just 100 yards from the Task Force Control Headquarters – where the hunt for him was being directed from.

The 17 day manhunt, which in total had involved 4,293 officers from 12 different police forces, and had cost £347,000, was over.

Who was Barry Peter Prudom, and why had he embarked on such a rampage? Born in 1944 as the illegitimate son of dressmaker Kathleen Edwards and soldier Peter Kurylo, Barry never got to meet his father. His mother married a man named Alex Prudom in 1949, and Barry took his stepfather’s surname. He spent his early years in a terraced house at 39 Grosvenor Place, Leeds, and was educated at the local Blenheim Primary School and Meanwood Secondary School. By no means academic, he nevertheless showed promise at sports, where he was described as being especially good at boxing and cross-country running. Prudom’s youth was punctuated with bouts of minor criminal activity and mischief, but never anything too serious or involving violence, and his youth was otherwise unremarkable from many of his fellow classmates and contemporaries. Upon leaving school, Prudom managed to gain an apprenticeship as an electrician, and reportedly this was a role that he showed real promise and aptitude in, and could have had a successful career at. He married a girl two years his junior in October 1965, aged 21, and he and his wife Gillian went on to have two children, a daughter in 1966 and a son in 1970.

The year before his son was born, Prudom had enrolled in the TA SAS Volunteer 23rd Regiment that was based in Leeds. He had always been an enthusiast of firearms and the military, and not wanting to be part of a “normal” regiment, Prudom enrolled in SAS 23. He participated in many weekend camps and manoeuvres and was described as a fitness freak, but because he had an apparent dislike of discipline, was told he was unsuitable for the SAS. Bitterly disappointed, Prudom still retained his enthusiasm for a “mercenary” lifestyle. Police who searched his home after the manhunt found several survivalist textbooks – including one called “No Need To Die” – written by a tracker named Eddie McGee! It transpired that Prudom had attended at least one lecture given by Mcgee on the subject of surviving in the wild and living off the land.

Devoted to his family, Prudom worked hard to provide a good and prosperous lifestyle for them. He worked away in the oil fields of the Middle East to provide for his family, but in 1977 his wife Gillian left him and took their children after she had had an affair with a neighbour. They divorced soon afterwards. After the divorce was finalised, Prudom met a girl called Carol Francis, who was half his age, and the couple took up a nomadic lifestyle, drifting around the country from place to place. Both would only occasionally work, with her taking sporadic employment as a waitress whilst he worked periodically on oil rigs. The couple then went to Canada to adopt the same lifestyle, followed by a period in the United States, before returning to the UK and settling down to an existence in a mid terraced house in Leeds, not too far from where Prudom had spent his early years.

It was the period spent in the USA that Prudom was able to obtain the pistol that he used in his rampage, a Beretta Model 71 Jaguar, smuggling it back to the UK when he and Carol returned in 1981.

The couple reportedly rowed lots, and after Barry attacked and severely wounded a 54-year-old motorist with an iron bar in January 1982 (the offence that he had not answered the court date for), Carol left him and returned to live with her mother. When Prudom’s name had been released to the media as being wanted for questioning, Carol made this appeal to the fugitive through the media:

“Barry, if it is you that the police are looking for at Malton, I would like to appeal to you now to give yourself up, before anyone else gets hurt. So please stop this now. If it is you they are after, I would like to see an end to it now before matters get worse. So listen to what the police are saying, and do anything they say for the good of all”

Police Chief Constable Kenneth Henshaw of North Yorkshire Police issued this statement to the public:

“Under no circumstances should anyone approach this man. He is a dangerous, ruthless, callous individual who will not hesitate to shoot at anyone. Anyone who approaches him is in extreme danger of being killed – he is obviously a trained marksman”

What triggered Prudom to initially kill has never been clearly ascertained, but Prudom’s mind had seemingly snapped after Carol had left him, and he had brooded and fantasized throughout the subsequent months until he had left his Leeds home that mid June, armed and mentally ready to kill. He was never to return.

The inquest that opened in Scarborough on Thursday 7th October 1982 called several witnesses to it, including PC’s Oliver and Woods, Mrs Sylvia Luckett, and several witnesses who had seen the shootings and had encountered Prudom throughout the manhunt. But it was perhaps the evidence given by the Johnson family that best offered an insight into Prudom’s rampage. Mrs Bessie Johnson, who had been held hostage along with her husband and son on the final night of Prudom’s rampage, told how she had been surprised in her kitchen by Prudom, who had pointed a gun at her and said, “You know who I am, don’t you?” She replied that she didn’t, and Prudom had marched her into the sitting room at gunpoint, and tied her and her husband together with string. He had then cooked fried egg and bacon, but had been disturbed by the Johnson’s 43-year-old son. The son was also tied up and Prudom told him:

“You stupid bastard..if you had run the other way I would have shot you.”

Once all three had been securely tied up, and having seen himself on a television news bulletin and learned that a tracker was searching for him, one whom he knew and expressed admiration for, Prudom told the Johnson’s of his exploits over the previous weeks.

Mr Johnson related how Prudom had described the shooting of PC Haigh:

“I was in a clearing and had been asleep all night in the car. This policeman approached me and questioned me, he mentioned something about me hitting a man with a bar in January. He was going to take me in, so I immediately shot him” – Barry Prudom

Prudom then described how he had moved to Lincolnshire and broken into the home of Mrs Jackson and tied her up, but knew that she would be released the next morning when the bread delivery driver arrived. Next, Prudom told the Johnson’s how he had travelled on foot to the village of Girton, where he had broken into the Luckett’s home to steal their car. He claimed that he had shot the Luckett’s in self-defence after George Luckett had pointed a gun at him. He had then fled in their car, the number plates of which he had substituted stolen ones for, and driven up to Bickley Forest, where he got lost. This was the night that Prudom attempted to kill PC Oliver, and it was following this that Prudom made his way to the Malton area, living rough in the forest hide for a number of days. He had emerged from his hide and entered a shop in Old Malton to buy sausage rolls and bread, but had been reported as suspicious by a member of the public.

This was the day Prudom had shot and killed Sgt Winter. He told Mr Johnson:

“I heard one copper shout “Watch it, Dave!”.The policeman climbed a wall and I caught up with him. I thought, “I will have this bugger” and shot him. I feel sorry in a way but not really. He was a policeman” – Barry Prudom

He then untied the Johnson’s hands and told them he would be leaving in a few hours, but Prudom finally left the Johnson’s house at about 5:00am the next morning. He had taken food from their larder, which he perhaps prophetically described as “My Last Supper”, and had armed himself with his pistol and a two foot machete.

Throughout the night, each member of the Johnson family had tried in vain to appeal to Prudom to give himself up, but each time he replied that he would never let the police take him alive. He vowed to take his own life and as many police officers with him as possible before that would happen. He had nearly 60 bullets on his person as a testament to this claim. His final words to the Johnson’ before leaving were:

“I am going to die but I will not be the only one. There is nowhere for me to go. Thanks for everything”

Dr Sava Savas, the pathologist who had performed the autopsy on Prudom, noted that Prudom’s feet were badly swollen and bleeding, supporting the view that he had been exhausted and had been kept on the constant move by the manhunt. He also found that although there were 21 separate injuries to his body that had been caused by pellets as a result of police fire, the two main wounds were a shotgun pellet in Prudom’s forehead, and a bullet inside his head that had been fired into the right side that was characteristic of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. It was Dr Savas opinion that either head wound would have caused instant unconsciousness, but that the more likely cause of death was the self inflicted gunshot wound to the right side of Prudom’s head.

A coroner’s jury supported this, taking just 18 minutes to record a verdict of suicide.

The focus of Prudom’s hatred seemed to have been directed at police, and it seems that his mind had finally snapped. Even if he had gone on the run to avoid what would seemingly be an inevitable custodial sentence for the January 1982 assault, there is no explanation for why he chose to add such an appalling catalogue of murder and violence. He was fit and an experienced outdoorsman, had proved that he was able to evade capture and was skilled at living off the land – he could clearly have gotten away with little or no bloodshed and may never have been recaptured. Yet Prudom proved himself ruthless – cold bloodedly shooting several people and never once just attempting to wound, or warning before shooting. It can be argued that he immensely enjoyed killing, and wanted to go out in some sort of blaze of glory. Yet in his final moments when confronted by the armed police he so wanted to kill, his nerve failed and Prudom took his own life. Following his death, he was buried in an unmarked grave in a Leeds cemetery.

The verdict of suicide brought a close to the case of Barry Peter Prudom, and the manhunt that had paralysed the areas where “The Phantom Of The Forest” had struck with fear. A manhunt that at the time was the largest armed police operation that the country had ever seen, involving over 12 police forces, resulting in 17 days that had gripped the nation.

The True Crime Enthusiast

Barry used to live just around the corner from me at meanwood, he was always a bit of a mystery because he wasn’t allowed to play out in the street with the rest of us, I remember him joining I believe it was the sea scouts near to Hyde Park at about the same time that I joined the scouts.

I lost track of him once he moved away from meanwood, but i never forgot him because I trained as an electrician as well.